Wednesday, June 28, 2023

*Note: This post contains a lot of historical and political information that was told to us directly by a person with a clear bias. I fact-checked afterwards with research of my own, but it’s still likely that I got things wrong. If you’re an expert in this area and have a correction for me, please let me know!*

This morning’s start is our earliest of the trip so far. We’re going to Northern Ireland today for a tour of Belfast and the Giant’s Causeway, and the tour leaves at 7:00. Oof. We navigate to the pickup point, a Starbucks at College Green near Trinity. We’re early, so we go in and grab some hot drinks to warm and wake us up, and then we get onto the bus. It doesn’t have hokey lettering or a large image of a leprechaun on the side, so I’d call that an early win.

Admittedly, we are a little nervous after the tour to Blarney Castle. That guide was just so bad, it was almost scarring. But as the bus departs and today’s guide starts introducing himself, we are cautiously optimistic. His name is Kevin, and he seems very cool. He is originally from Dublin but lived in Ecuador for ten years and is just now back. He’s studying to complete his degree in adult education, and he seems very passionate about history. I like Kevin. Kevin has good vibes.

We start driving north through the Republic of Ireland, which soon gives way to Northern Ireland, which is still part of the United Kingdom. Kevin points out that immediately after crossing, all the Irish language on signage disappears. Also, in Ireland—still part of the EU—the speed limit signs are in kilometers per hour, while in Northern Ireland they are in miles, England-style. There’s also a memorial just across the border with ten crosses and an Irish flag. Kevin says that the crosses represent the ten men who died on hunger strike in prison in the 80s protesting to gain status as political prisoners. I can already see, just from the border, that this is going to be an intense day of political and historical learning about this fraught corner of the island.

Our first stop of the day is in Belfast, the capital of Northern Ireland. We have a choice of what to do here: there’s a black cab tour that goes through the city and provides historical and political commentary, or there’s the Belfast Titanic experience. It’s not even really a question; Mom and I choose the black cab tour. The Titanic is fun and all, but you can get that information anywhere. Why not learn about the turbulent history of a place from a local, someone who has experienced it? To me, that’s what travel is for.

We’re dropped off at a shopping center for a coffee refresh and a bathroom break, and then we’re split up into smaller groups and loaded into the taxis. Mom and I are with an American couple also traveling around Ireland on their holidays. Our driver, Patrick, doesn’t say much as he’s driving, but he makes a few stops and has us gather around him while he launches into extremely detailed, intricate, and interesting political history.

Our first stop is in the Falls Road neighborhood. This neighborhood is predominantly associated with the Irish Catholics in Belfast. But really, from what Patrick explains, the religious divide in Northern Ireland is an inaccurate portrayal of the real issue. It’s a kind of shorthand more than a genuine distinction, especially in the modern age when not as many people are religious. “Irish Catholic” might more accurately be called “Irish Republicans” or simply “Republicans,” who associate themselves more with Ireland and think that the entire island should be united. “Protestants” might more accurately be called “loyalists” or “unionists,” and some of them are descended from the Ulster Scots who colonized the area during the Ulster Plantation beginning in the 1600s. Patrick’s point is that settlers from mainland Britain came in and created a divide that never existed before their arrival, and now that divide has been weaponized and capitalized upon. “Their strategy has aways been to divide and conquer,” he says of England. “Go in, make an artificial divide, and that’s how they win.”

Patrick is clear about his Irish Republican agenda, but from what Kevin later explains, there’s not a single person in Belfast who doesn’t strongly take one side or the other. That divide is still extremely apparent. The neighborhoods in Belfast are visibly segregated. “Catholic” or Irish republican neighborhoods are typically poorer and less resourced, and “Protestant” or unionist neighborhoods tend to be well resourced; they are also where the universities and good school districts are. Part of the role of Patrick’s organization is to taxi students from the poorer areas into the richer ones so that they can attend better schools and universities.

On the side of the Falls Road there is a row of murals depicting various events in the history of Northern Ireland. There’s a mural of the ten victims who died on Hunger Strike during the Troubles, along with an image of the most prominent of the ten, Bobby Sands, holding a flag depicting the Irish harp, under the line “Unity in our time.” In addition, there are murals referring to other nations and their struggle for freedom from oppressive rule, including Palestine. “It’s not just us; we stand with other nations,” Patrick adds. “We’re all in this together.”

Our next stop is the mural of Bobby Sands painted on the side of the Sinn Féin building. Sands is beloved around here, and is seen as a visionary leader, poet, and thinker. He was also elected to parliament while imprisoned and while on hunger strike. Sinn Féin is a political party associated with the Provisional Irish Republican Army that rose to national prominence during the hunger strikes in the 80s. In the 90s, Sinn Féin was involved in the peace process and helped to bring about the Good Friday Agreement. In 2022, for the first time in its history, it won the majority of first-preference votes.

While we’re looking at the mural, Patrick makes an interesting point about another visible difference between the republican and unionist neighborhoods. In more “Catholic,” Irish republican areas, he says, you won’t see flags flying. Instead, there is artwork. Meanwhile, in “Protestant” unionist areas, you’ll see the Union Jack flying everywhere. “We don’t really like to fly the flag,” he says. “We rely on art, on creativity, to get our message across. Flying a flag doesn’t send a good message.”

“That sounds familiar,” I comment, with a hefty edge of cynicism.

“Yeah, you have that problem with the flag in America, too, don’t you?” Patrick responds.

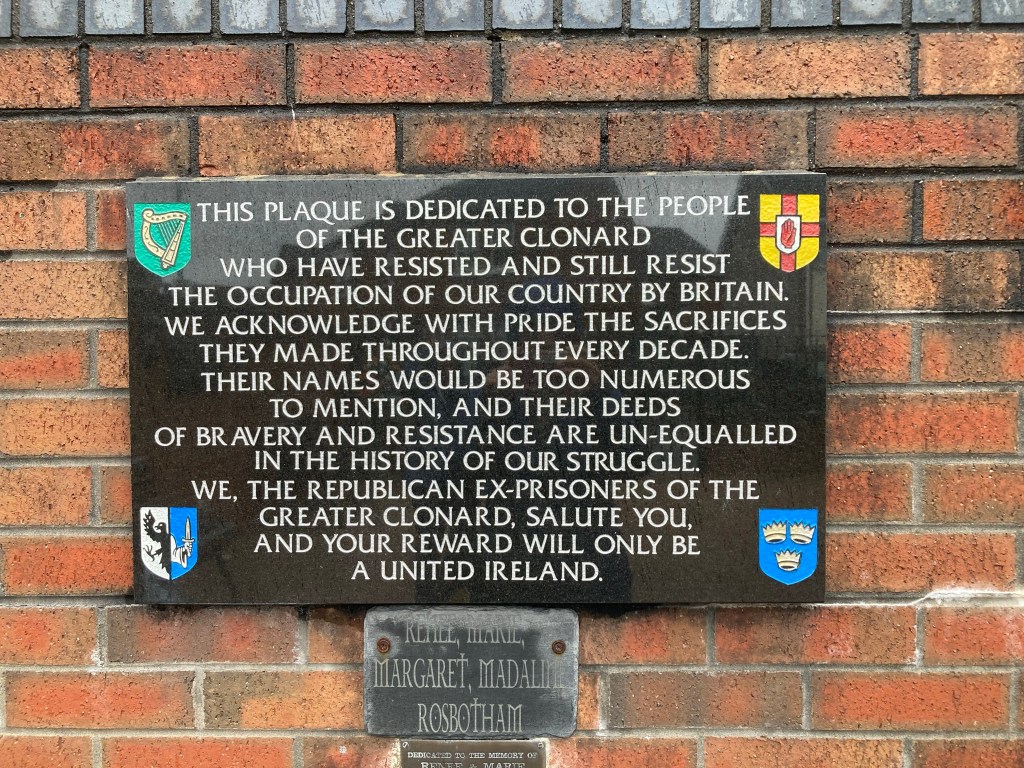

Our last stop is a memorial in another Irish republican neighborhood to people from this are who have been killed over the years in the conflict. Behind the memorial and the rows of houses, there is a wall. The main part of the wall is concrete, about eight feet high, and then it turns into metal, as though as an afterthought. Above it, there is fencing topped with razor wire. The houses have fencing angled above the windows, too. “Do you see that?” Patrick asks, pointing it out to us. “These houses had to add that because people in the unionist neighborhood beyond the fence throw things over the fence at the houses.”

“Still? Today?”

Patrick nods. “All the time. You never see Irish republicans throwing things over there, just the other direction.” He says it’s usually kids who do these kinds of things, teenagers, who have been taught in one way or another that people in the “Catholic,” republican, poorer neighborhoods are somehow less than them.

“The gates between neighborhoods are locked every night at eight o’clock,” Patrick adds. Then, when he sees the look of shock on our faces, and as if used to giving this answer, he adds, “It’s a young peace. It’s a tentative peace. We have to do that to keep the peace. One day, Ireland will be reunited. 10 years, maybe. But it’s not there yet. It’s a young peace,” he repeats.

My head is spinning when we get back in the taxi. Now that my eyes have been opened, I can see it everywhere: the fences, the razor wire, the security cameras, and beyond, always, the Union Jack flapping in the wind. It’s easy to write off this kind of conflict as either having happened far in the past, or only happening in “bad” areas, or maybe countries that are former colonies, or, perhaps non-white countries. But Belfast is a striking visual reminder of the lasting, recent, and modern history of colonialism and conflict. I can’t help but keep thinking about what Patrick said about “divide and conquer,” and how this was England’s winning strategy, how they were able to take over so much of the world. How to conquer? Make an artificial divide, and watch it burn.

Patrick drops us off at the Titanic experience, where we’re meeting back up with the other members of the tour. We thank him profusely and wander into the enormous building in a daze. This is clearly a unionist part of town, well-resourced. This building is enormous and posh, and the apartments and skyscrapers in the area look pristine, brand-new, expensive. It’s a bizarre divide, and it’s uncomfortable to be in here after what we’ve just seen. We get a quick lunch at the café, then meet back up with Kevin and the rest of the group.

Our next destination is Dunluce Castle, the ruins of a medieval castle that was once the seat of the MacDonnell clan. It’s in pretty good shape as far as ruins go, though, and it’s an enormous complex that clings to the land at the edge of the sea. It was the inspiration for the castle on Pyke of the Greyjoys in Game of Thrones. It doesn’t really bear that much resemblance to the fictional version, but I can kind of see it when we walk over the bridge that connects the two parts of the castle. Kevin takes our photo next to the window and then points out several land masses in the distance: to the left, and the west, the far northern tip of the island, which is actually in the Republic of Ireland, not Northern Ireland. And to the right, the northeast, the edge of Scotland reaching down into the sea.

We load back up into the bus after a quick spin and wind up at the other major destination for the day: the Giant’s Causeway. It’s an infamous place; here, right on the edge of the coast, lava cooled into hexagonal basalt columns that rise at varying levels as if straight out of the sea. Kevin gives us the lowdown on various paths to take, recommending the cliff path followed by the lower path along the water. We hop out and take his advice, climbing up onto the cliff path above the Causeway.

We come upon a young woman who’s traveling alone and asks us to take her photo at various viewpoints. I ask where she’s from, and she says New York City. We get to talking and she, mom, and I walk the rest of the hike together. I ask her name, and she responds, but I’m not sure how to spell it. My best guess is Anika, with stress on the second syllable: Ah-NEE-kuh. She’s super interesting; she’s a doula and a project manager and also tutors kids part-time. This is her first big solo trip, and after Ireland, she’s heading to Amsterdam.

We follow a steep staircase down, and it starts to rain, but before long it lets up and it’s sunny again. We take a side path that leads us into a cove lined with cliffs formed of the same basalt as the coast below. We all gasp when we see it. How is this place real? That feeling of this-is-not-real follows us as we descend towards the main part of the Causeway. The waves crash against columns of varying heights and pull back; the effect is a gradient of dark gray to an ash color against pure blue water. It is unreal, an indescribable landscape. There are people everywhere, and it’s impossible to get a photo without them, but it’s one of the most unique sights I’ve ever witnessed.

When we get down closer to the water, there’s an emergency team there heading over to where a person has apparently fallen. No one seems to be in a huge rush so I’m assuming the person is okay, but we see a stretcher at one point, so that’s scary. It makes me walk a lot more carefully on the slippery rocks while I’m taking in the formation.

We realize with a start that it’s later than we thought it was, so we start booking it back to the bus. I have to run, literally run, to the bathroom, then I meet back up with Mom and we load up. It doesn’t look like we’re the very last ones, though, and Kevin doesn’t seem surprised that we took the full amount of time; it’s an amazing place, after all. This is one of the disadvantages of these day tours, though, I will say. It’s the only way I could think of to get to these places without having to rent a car, and it’s nice that they plan everything and take you around. But it’s frustrating not to have as much time as you want in a place. Ah, well. We got to see it, the weather was phenomenal, and now we get to settle in for a beautiful drive.

On the way back, we stop at a viewpoint overlooking the water and, in the distance, Rathlin Island. Closer, we can also see Carrick-a-Rede rope bridge precariously perched between the cliffs of the mainland and a small island that used to be home to a fisherman. Kevin says that this tour company used to take people there, but then the organization decided to no longer allow coach busses through. Ah, well. We still saw so much today. I’m overwhelmed by and thankful for the experience.

I have a tough time staying awake on the long drive back to Dublin. When we do return, we thank Kevin, say goodbye to Anika, and start a quest for dinner. After encountering many closed restaurants, we come upon a cute pub called Bruxelles, where we sit outside and have a lovely meal of salad and curry, and a pint of Guinness for me to finish it off. Then it’s a nice meander back to the apartment. I’m starting to get used to our little place on Hatch Street Lower. I think I could stay here.